“Viceroy’s House”: Indian Independence in “Upstairs/Downstairs” Story

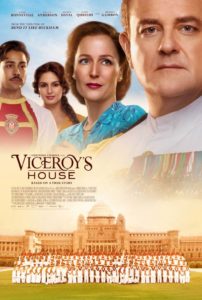

(Gerry Furth-Sides) Gurinder Chadha’s VICEROY’S HOUSE film is as transplendent as the palatial New Delhi home of the same name in 1947 when India was indeed the “Jewel in the Crown” of the British Empire. The film begins with it newly occupied by the recently dispatched Lord Mountbatten and family to oversee India’s complicated move to Independence.

It is obvious that Mountbatten (a more jowly, jolly Hugh Bonneville than Louie), has shared such arrivals at former posts with playgirl wife, Edwina (British-brittle Gillian Anderson), and daughter Pamela (Lily Travers) but never grander than this one.

With co-screenwriters Moira Buffini and her husband, Paul Mayeda Berges, masterful storyteller Chadha (Bend It Like Beckham) sets her tale in the ever-popular “Upstairs/Downstairs format. The idea: to bring in the perspectives of both the privileged British and Indians who worked in and resided near the elaborate house.

Chadra, in fact, was able to talk to Pamela Mountbatten and also to Lord Mountbatten’s aide-de-camp and author Maharajah, Narendra Singh Sarila extensively. Sarila revealed how Indian luxury at the time even contrasted with England still suffering war-rationing. When servants brought in a gleaming silver tray of beef for the Mountbatten’s pet dog the first day, they were tempted to eat it themselves!

VICEROY’S HOUSE succeeds beautifully in portraying the opulence of the time and the “pomp and circumstance” personality of Mountbatten, determined always to “act honorably,” if not knowledgeably. (as the photo below shows).

The socialite world of the Mountbattens turned upside down in India, brings out an altruistic side of Edwina, who incorporated Indian culture into the HOUSE, and who forged a lasting bond with Nehru.

Untangling the political story, though, is not as easy, and would add another hour as it did in the sprawling film, GANDHI. In short, British India’s 300-year imperial policy of divide and rule had flowered into evergrowing sectarian violence with profound effect. By the end of the second world war, the 300 year-old empire was politically and economically untenable.

Bickering leading to outright brawls between Hindu and Muslim staff in the VICEROY’S HOUSE is representative of this. As the split of India looms near, the house and its contents are divided between the new states of India and Pakistan, each side quarreling over the silverware and the library books – perhaps symbolizing perhaps the larger political conflict about lines drawn for the invaluable Kashmir region.

In Chadha’s evaluation, the British “worked their Black magic” to divide the country. “They ruled my homeland efficiently and ruthlessly, and my ancestors supported that rule, holding senior posts in the British-Indian police force and army.” Add to that the high levels of education of the political players, most of them barristers.

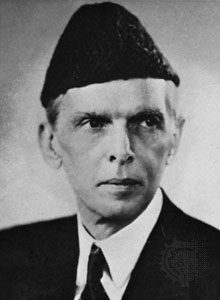

Political leaders, Nehru (Tanveer Ghani), Muhammad Ali Jinnah (outstanding Denzil Smith) and Gandhi (Neeraj Kabi) are shown in the film to be strong characters with singular ambitions, responsible for generations of political history.

The film entices another viewing of the brilliant (historically accurate) character story of JINNAH with Christopher Lee. It explains that Jinnah was a barrister first, not a politician dealing with the then-restrictive Indian elections and that a nation cannot be created out of a religion and MJ Akbar tells the story here. http://(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4zYsfrkjsJE)

Finally, “partition” at film’s end balanced out the measured opulence of the VICEROY’S HOUSE. It erupted into the most horrific refugee crisis, as a result of sectarian violence, starvation and disease. Close to four million people were displaced, and up to a million died in the largest mass migration in human history,

Partition left a lasting shadow over one family, Chadha’s own. In the VICEROY’S HOUSE closing credits, Chadha dedicates the film to her grandmother, who survived the devastating upheaval. Fforced to walk a vast distance from her home to the new Muslim republic of Pakistan, she left her young daughte in a river who starved to death en route, and was finally reunited with her eventual husband in a refugee camp. Chandha: “This had an impact on the family forever.”Wouldn’t the refugee story of Chadha’s own family be more focused, genuine and meaningful than the Romeo-Juliet soap opera of the film?

However, what Garinder observed growing up contradicted such sectarian violence. Her dad had longstanding customers in his corner shop in London who would “come round in the evenings to keep him company. Most of them were not fellow Sikhs but Muslims from his ancestral town.”

And when she traveled to Pakistan to find her grandfather’s home for the BBC’s “Who Do You Think You Are? program in 2005, she received a heartfelt welcome by the refugees living in it. They made her “realize the humanity” of those caught up in a situation. At that point she vowed to make the film.

An account of her later meeting with Prince Charles gives another version of this story, revealing how changing one fact in an incident can alter written history. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/28/revealed-quiet-word-prince-charles-convinced-director-make-film/

Directed and Produced by Gurinder Chadha. Written by Paul Mayeda Berges and Moira Buffini (Screenplay).

The film’s score is from Oscar-winning composer A.R.Rahman.

Keith Madden created the meticulous costumes. (For me, Nehru’s iconic, timeless “Nehru” coat remains the star)