“WHITEY: United States of America v. James J. Bulger” June, 2014

“WHITEY: United States of America v. James J. Bulger” has the all the makings of a strong suspense film, from the opening shots and Wendy Blackstone’s music that pull you right in and don’t let go even after it ends. It lays out a fascinating, elegant story of the American mob scene and U.S. judicial system relationship – but leaves the viewer with a lot of questions even when it is over.

Credit for the phenomenal look and feel of this compelling CNN documentary belongs to Academy Award-nominated and two-time Emmy and Peabody winning filmmaker, Joe Berlinger. Alex Horwitz and Joshua L. Pearson edited.

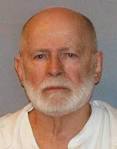

“WHITEY” begins with a media montage of the news reports following James “Whitey” Bulger’s 2011 capture in Santa Monica after 16-years on the run. As a Los Angeleno who lives and frequents Santa Monica (my colleague lived on the block next to Bulger and girlfriend, Catherine Greig), the capture also meant we could have been in their company without knowing it.

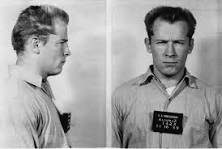

Turns out, who wouldn’t want to know about this powerful, good-looking guy “who got away.” Was he really, as he said, “reformed because of his girlfriend,” and is that possible? Upon his capture, he claimed he would plead “guilty to anything as long as they let Catherine go.” Whitey made a similar deal in his youth and would up with 20 years in Alcatraz for a burglary –inadvertently avoiding the mob wars at home. So here we have a tough guy and a gentleman.

Allowed only photos, film and voiceover in the documentary, Berlinger’s Bulger comes across as collected, candid and appreciative of the ironies in his case. “I’m the injured party,” he laughs at one point after his former partner Steve Flemmi testifies against him. “I never said a word about him.” Whitey, with his striking platinum hair, is the acknowledged “godfather,” whose brother was former President of the Massachusetts Senate, Billy Bulger. (I also thought I misheard at first when Whitey’s right hand thug mentioned that his own two brothers went to Harvard.)

As fascinating as Whitey’s character is in becoming a mob boss, so is the question of why he was “tipped off” 16 years ago. Was he an informant in the mindboggling FBI informant system, detailed by the film, in which criminals can trade their testimony for freedom or better prison accommodations? The government can also quiet and get rid of their own when as they please. Shades of Oliver Stone.

And Whitey, indeed, is more concerned in the two-month 2013 racketeering trial about proving he was not a paid FBI informant than about clearing his name of the 32 felony counts, including 19 alleged murders. He claims he paid the FBI for information and he protected them. Thus, Whitey is a “criminal with standards, a gangster with scruples.” He never “ratted” on anyone. On the civilized side, Whitey paid people off whenever possible, earning him the name, “the Robin Hood mobster.” On the uncivilized side, when they were a threat he killed them.

There is, of course, no written evidence for his claim, though the film makes a good case for him. And it was not proved in court, where Whitey never took the stand. Research and books still label him “an informant.”

Berlinger’s documentary is brilliant – clear and incisive, equal-handed. He sets the scene in South Boston, tough, mob-run, “Southy,” a movie character in and of itself. The individuals interviewed are also down-to-earth, blunt, good looking, active, no “talking heads” with a flower vase behind them.

In fact, the family of the victims’ open and close the film. One relative, the brother of Whitey’s victim’s still grieves his sister who was murdered 30 decades earlier for the crime of being Whitey’s partner’s soon to be ex-girlfriend. There is a lot of give and take about whether Whitey or partner, Steve Flemmi, killed her. A more unrelated “crime motive” is the murder by Whitey of the neighbor of a mob member, who was simply “in the way.” In typical and astonishing circumstance, one of the extortion victims is killed right before the trial.

James Whitey Bulger’s rise to dazzling long-standing reign over South Boston, as part of the organized crime system and the extensive web of characters in it, is made clear with footage and a photo diagram. Journalist, former State Police, FBI and Justice Department interviews fill in the story.

Berlinger sums it up best,” on Whitey Bulger’s possible links to the FBI. Look, I’m not saying whether he was an informant or not an informant, but I think it’s intellectually dishonest to just shut down the discussion. …Hey, if he was an informant, we still don’t have enough information as to how this was possible and who is responsible. And if he wasn’t an informant – man, there are some really deeply troubling questions.”

“Memory is a political act” is the line I like best. And finally, I wondered after seeing the film, did we really have something to fear as a neighbor in Santa Monica of this “old man” these past 16 years? I would have to, in the end, answer, “yes, we would.”